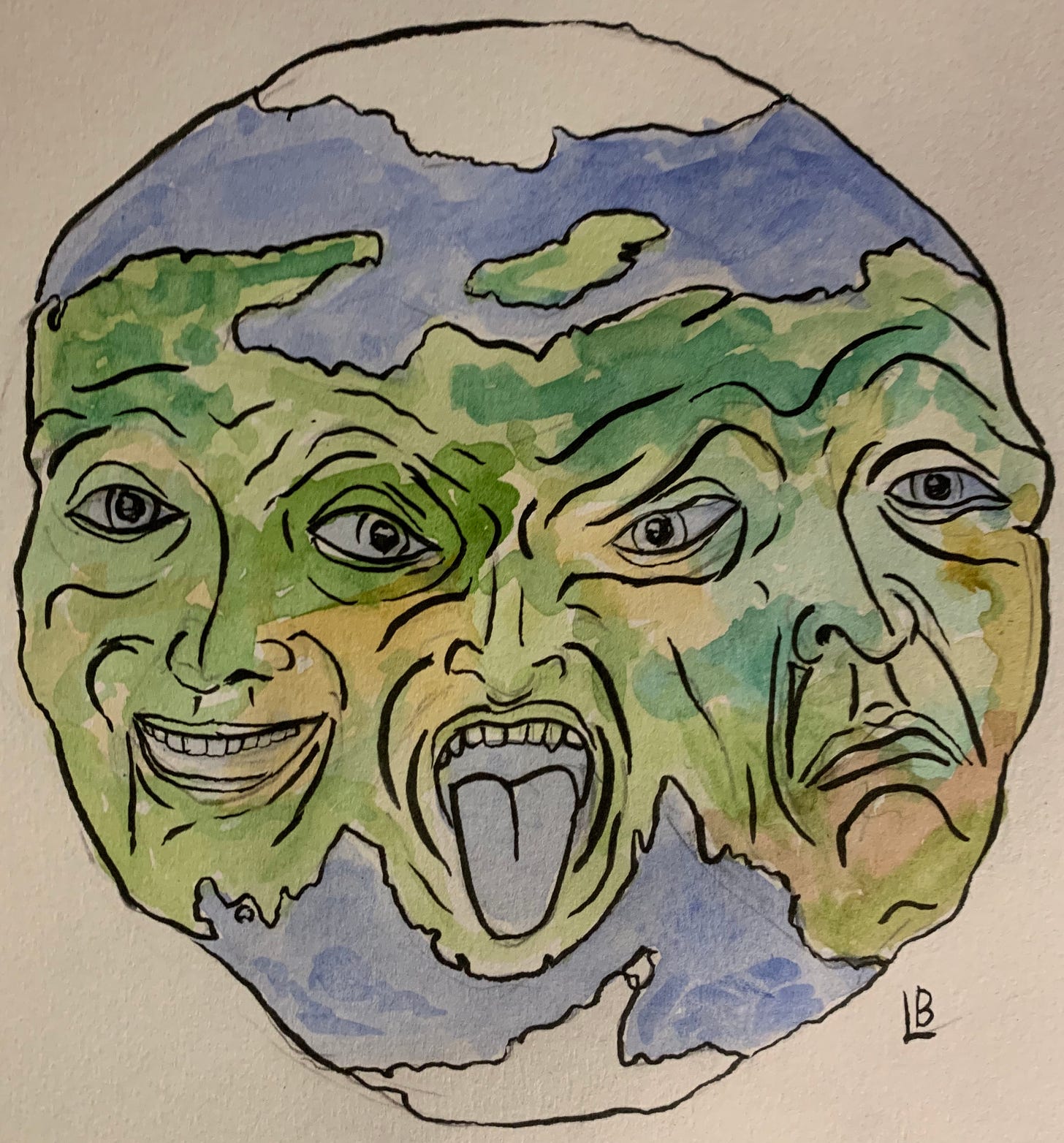

Climate Tech's Identity Crisis

Awkward teenage years and the future of planetary technologies.

Recently, conversations with friends and fellow travellers in the climate tech world have been filled with uncertainty. Many anxious hands have been wrung in the wake of the ascendant Trump White House, with some wondering whether Uncle Sam will turn off the subsidy taps, spelling doom for current efforts and the industry. Last December, another ineffective COP avoided profound breakthroughs in multilateral climate action.

This phase of introspection may also stem from climate tech’s adolescent growing pains. As the sector gradually emerges after a painful downcycle, it feels clear that we are entering a phase where difficult questions must be asked.

Common in adolescence is an identity crisis.

I know I may be adding fuel to the fire, but several blogs (see, for example, Sifted) and editorials have agonised over the "climate tech" label. Several venture funds have jettisoned the term. It is easy to dismiss labels as unimportant or a distraction, but understanding them can tell us something about the movement's underlying structure. We must understand the structure of what climate tech has become in recent years.

The Death of Cleantech, The Emergence of Climate Tech

“Cleantech 1.0”, approximately 2006-2011, focussed on a narrow totemic set of energy technologies (solar PV, wind turbines, biofuels). Driven by a rising tide of optimism about renewable technologies. From 2007 conditions became more challenging as low natural gas prices undermined the business cases of many of the startups in the space.

The bubble burst, and many investors lost a lot of money. Post-mortems have revealed several systemic problems that caused the downfall of cleantech (see, e.g. Bessmer and this canonical MIT working paper), including assumptions that clean technologies could rely on charging higher prices for commodity products.

Nowadays, when one sees the label "cleantech", it feels like a relic of a bygone age. It is often still used by initiatives tied to government, where cleantech may sound like a more expansive label, but it is somewhat déclassé amongst private sector actors due to its association with failure.

The emergence of climate tech followed the decline of the cleantech era, marking a significant shift in the industry's approach. This transition was largely enabled by the dramatic reduction in core technology costs, primarily driven by scaled production in China – a development that was ironically supported by Western cleantech-era policies such as German Solar Feed-in-Tariffs.

Never underestimate humanity's ability to get very thin sheets of silicon to do amazing things or the ability of the Chinese to leapfrog complacent Western industry leaders.

These cheaper technology costs created the necessary preconditions for the new climate-tech boom. Unlike its predecessor, climate tech doesn’t focus primarily on developing core technologies like solar PV and wind. Instead, it concentrated on deploying these maturing technologies and building systems around them.

The sector's growth was further accelerated by increasing public awareness of climate challenges, which drew talent and money into the field. Additionally, government incentives began to extend deeper into various economic sectors, creating numerous niche opportunities for decarbonisation that companies were eager to pursue.

Climate Tech Exuberance

The wave crested between 2021 and 2022 at around $78bn of equity funding flowing into the category.

Private investment declined precipitously in 2023. Though much of this was covariant with a general down-cycle in venture markets, it is clear that other forces are at play. For example, many low-carbon technologies are capex-intensive compared with fossil-powered equivalents (which are generally more opex-intensive). In high-interest-rate environments, low-carbon can be at a structural disadvantage.

High-profile failures, such as Britishvolt and Northvolt, added to a sense of gloom (it may be high time to retire 'volt' as a suffix). 2024 saw improved total investment amounts, though some massive later-stage debt rounds and government subsidies propped up much of this activity.

We are now seeing some of the ghosts of Cleantech come to haunt us. Again, Chinese industry is leapfrogging Western competitors regarding quality and price in strategically crucial technology areas like battery and electric vehicle manufacturing. Again, firms may have relied too much on altruism to drive spending decisions. Again, too few have focussed on fundamental unit economics.

The Internal Contradictions of Climate Tech

A key challenge for climate tech is that it creaks under its internal contradictions as a technology category.

Firstly, the term has become inflated.

As climate action has (slowly) permeated the economy, technological solutions to different decarbonisation challenges have multiplied. However, this success has resulted in inflationary pressure on the term climate tech. Trivially, anything that improves efficiency in energy or resource usage may have a carbon benefit and can, therefore, be called climate tech. In recent years, I have seen all sorts of ideas masquerading as climate tech trying to capitalise on the caché, from AI-enabled pizza ovens to slightly more efficient internal combustion engines.

It has also become a synecdoche for other kinds of technology solving environmental challenges (biodiversity, water pollution, etc.), even those not directly related to greenhouse gas emissions and management. Clearly, these crises are deeply interlinked, but the conflation is confusing.

Secondly, Climate Tech does not have a coherent talent pool. In tech categories and ecosystems, the community of engineering practice that firms draw upon is key. Tech sectors often thrive around a core group of engineering talent, creating an ecosystem where tacit knowledge flows freely between companies as employees move between companies. This can lead to the formation of clusters of expertise, where the early employees of a prominent company in the sector help to seed the next wave of startups and innovation (sometimes cringe-worthily referred to as mafias). Examples of this abound, from the early days of Silicon Valley’s tech industry with semiconductor expertise and the traitorous eight leaving Shockley Semiconductor, to Boston's biotech ecosystem.

Climate Tech, on the other hand, spans a wide variety of solution and technology groups, many of which have little to do with one another. It spans, amongst others, electrochemistry, materials science, chemical engineering, and synthetic biology.

Thirdly, Climate tech does not service any industry vertical in particular.

In some industries, the pathway from startup to exit may be well-trodden, such as in drug discovery, where the milestones needed to be hit are generally well-characterised (e.g. clinical trials), and the exit routes shine gloriously on the horizon (e.g. big pharma). In other sectors, such as proptech or agritech, the routes to scale may not be as well-trodden. Yet, insider knowledge and experience are invaluable in helping entrepreneurs navigate the early stages of company formation.

Climate Tech, on the other hand, services no particular vertical. Energy, broadly defined, and transportation indeed make up the lion's share of investment that goes into climate tech. However, these are not confined to any particular industrial sector. Venture investors and others looking to provide the support structure to climate tech companies are, therefore, effectively generalists. However, I note laudable recent efforts that crystalise some of the learnings about these pathways (see Climate Brick and Building and Scaling Climate Hardware: A Playbook).

Looking at Climate Tech from afar

The culture in climate tech certainly has something of viewing solutions to problems from the bottom up. This is especially true in the early stages of company development, where you can daydream about what such and such a widget might achieve for the world. I, for one, love the frisson of seeing elegant technological solutions to knotty problems and imagining how they might become a reality.

It is helpful to take yet another step back and see climate tech from a distance.

Climate tech is best understood as something like a social movement - one part normative around the use of one’s labours to achieve altruistic ends, and one part an opportunistic push towards a particular set of enormous economic opportunities. As a social movement, it has matured into developing institutions, (underpowered) lobbying infrastructure, conferences, newsletters, clubs and events.

Setting aside the moral imperatives of investing in world-saving technologies (if that is indeed possible) for the moment – what is the commercial logic of climate tech investing?

Investors (or Limited Partners) are looking to benefit from a set of attractive underlying dynamics when assigning capital to climate tech. The high availability of motivated talent that has moved into the climate means that firms can hire quality human capital at a discount. Regulation from governments and industry-led initiatives has elevated decarbonisation and climate risk management to the top of the agenda for many powerful corporations. Massive subsidies, such as those in the Inflation Reduction Act, benefit companies in this space, with climate tech firms often enjoying favourable regulatory environments due to their public-spirited missions. The energy and energy services markets are extraordinarily large—energy is the world's largest industry—with total addressable markets that fit the venture model perfectly. Moreover, the boldness of founders seeking to reshape the world in this space generates genuine excitement about the potential for supernormal returns.

All of these dynamics are genuine and still exist. However, in practice, picking a basket of high-growth equities that representatively and reliably capture these beneficial dynamics is challenging. For unintended reasons, funds operating in climate may end up with very strangely skewed portfolios exposed to very particular risks.

Take, for example, how investment theses operate in practice. Some climate tech investors, in seeking significant problems and markets, assign a "megatonnage" of CO2-equivalent screen to their investments (i.e. is this startup solving a large enough carbon problem). This is a laudable measure, but one that may bias investments towards high-risk, long-term technological moonshots (like Direct Air Capture) that may take decades to materialise and away from low-hanging fruit. This, therefore, not only adds technical risk to the portfolio, but also market risk, seeing as many of these technologies rely on markets that are nascent or relatively illiquid (like voluntary carbon markets).

In addition to this, we must recognise that excitement in an investment theme amongst LPs may be “downstream” of events at the technological frontier and, therefore, may lag opportunities. By the time generalist investment categories like climate emerge, the alpha of early movers trying to harness the beneficial dynamics described above may have all but evaporated.

Given the generalist nature of climate tech, there is no singular, unified approach to how it operates in practice. This is particularly evident when looking at how climate tech is approached across various regions. For example, my conversations with investor friends in the UK, the U.S., and Europe around the topic of impact all sound entirely different. This can sometimes lead to “epistemic gerrymandering”, where fund strategies and definitions of impact are retrofitted onto portfolio strategies as a legitimising tool.

Into the Crystal Ball

Permit me to stare into the misty, near-emerging future and speculate a few scenarios as to what might happen next.

The climate tech movement may become increasingly kaleidoscopic, with entrepreneurs and investors organising themselves into more coherent categories—either clustered around specific technological groupings (like electrochemistry or synthetic biology), which would allow beneficial spillovers between firms. Alternatively, they may align themselves to service particular vertical markets (e.g. agriculture, built environment, chemicals) and become more like sectoral categories.

One emerging trend already seen is the alliance of climate tech with other narratives in the zeitgeist.

For example, we have seen the tentative fusion of climate tech with ascendant economic nationalist narratives and narratives around reindustrialisation. Clean energy at zero marginal cost of production represents an extraordinarily attractive proposition. Solar panels' rapid deployability and inherent characteristics align closely with the imperative of economic dynamism (see e.g. Max Bray’s Climate Dynamism). Moreover, local energy and resource production offers a compelling mechanism for loosening dependence on unreliable and geopolitically exposed international supply chains. Another example is the merging of climate tech with defence-sector investment under the theme of resilience.

We may also witness a strategic retreat into the "core" aspects of the energy transition, with a deeper, more focused approach to electrification and industrial decarbonisation. Perhaps this would be best labelled as “energy transition”, as it was in the old days.

All that said, perhaps little changes and for all the fears that climate tech might falter, the movement proves resilient. Perhaps the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, has embedded climate policy so profoundly in the U.S. political economy, much like the Affordable Care Act before it, that wholescale reversal from the Trump administration proves impossible. One can take solace in the fact that an eccentric electric car salesman is the power behind the throne of the new regime.

Keeping eyes on the prize

Critically, those of us morally and personally invested in deploying carbon-emission-reducing technologies must contemplate the ultimate commercial goal of our labours. Anecdotally, I have heard palpable frustration among some Limited Partners about the climate tech movement's relative insularity and estrangement from fundamental return dynamics in recent years.

As William Janeway wonderfully illuminates in "Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy", tech movements require speculative momentum in the broader economy to generate reliable IPO environments. This tech speculation is certainly wasteful, in a Schumpeterian sense, but is ultimately benign so long as it avoids leaking into credit markets. We might wish to think about which technologies may ignite this speculative fever, like nuclear fusion, perhaps.

In the absence of buoyant IPO markets, investors must become more adept at steering companies towards meaningful M&A events – a trend already emerging and perhaps underpinning the current fascination with "deep tech" opportunities with IP that can be developed for strategic acquisition.

The opportunities in decarbonisation, electrification, and adaptation remain gargantuan. Overall, it may not matter whether a community called climate tech continues to exist. It may sublimate or find itself absorbed into the broader economy – in the future, one might hope that every company is in some way a "climate company".